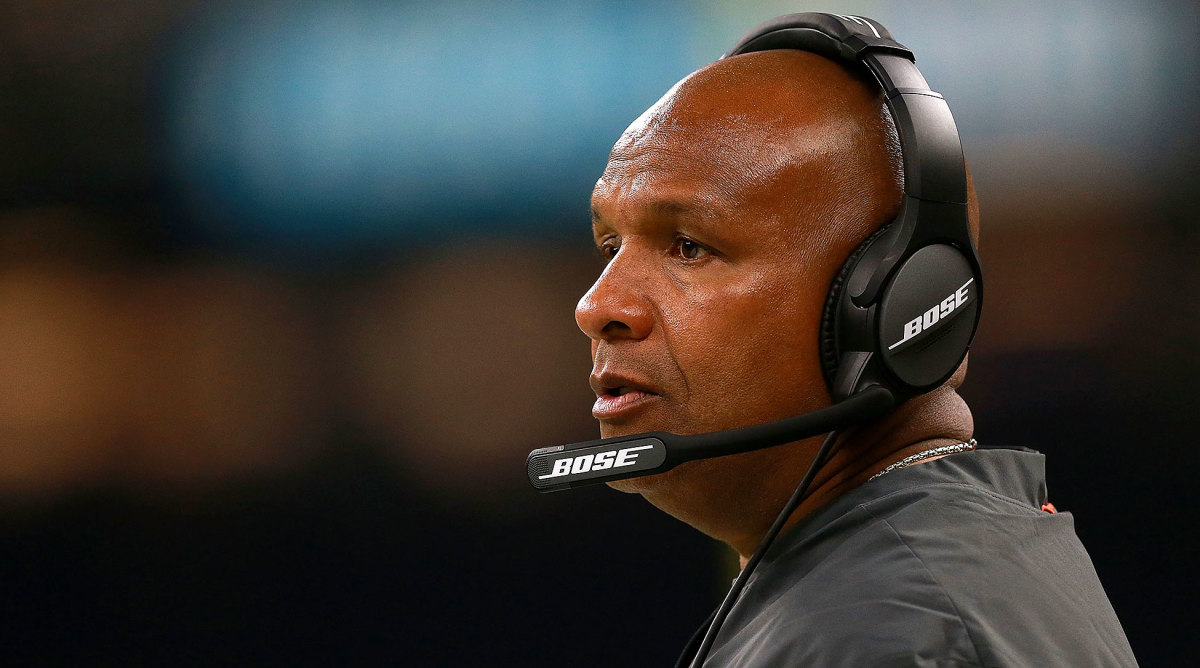

'I Failed Tremendously': Hue Jackson on the Blues After the Browns

To watch The Big Interview: Hue Jackson in its entirety, plus the rest of the The Big Interview series and more original SI programming, go to SI TV for a free seven-day trial.

A version of this story appears in the Aug. 26–Sept. 2, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

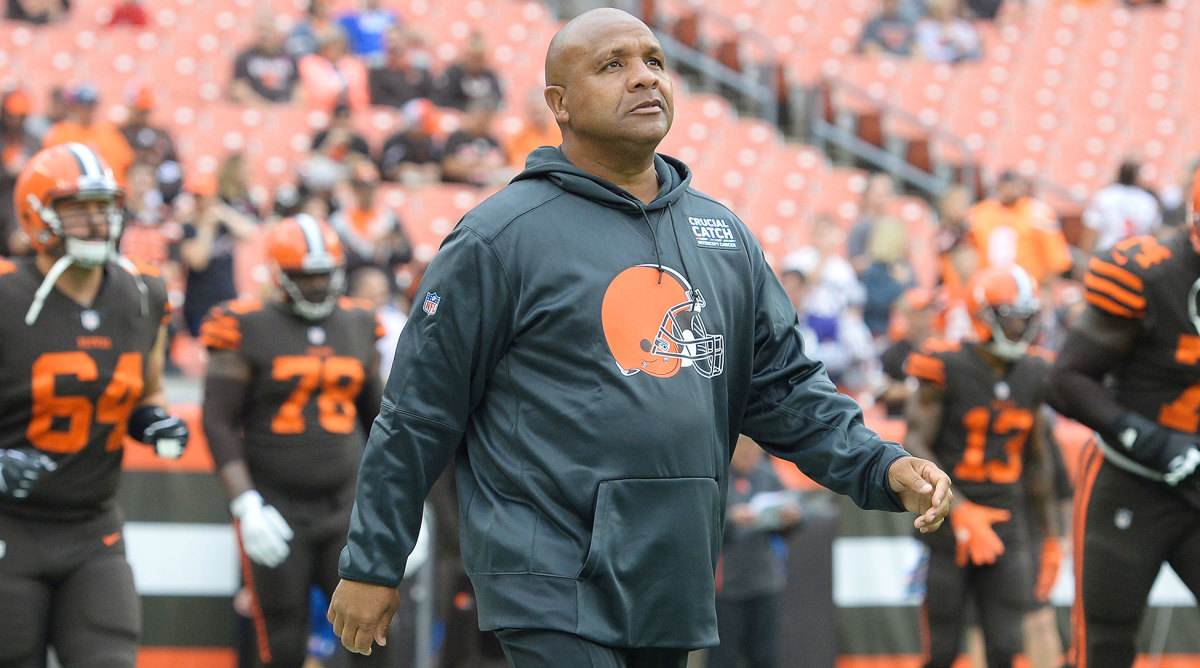

On the worst day of the worst year of his life, Hue Jackson told his team’s owner and general manager to “get the f--- out” of his office. After the Browns fired him last Oct. 29 he grabbed a few things and left the facility, never to return. Then he drove as fast as he could, windows all the way up, no radio.

He called his wife of 24 years, Michelle, and filled her in. At home he went down to their basement, turned off the lights in the guest room and stayed there. For three days. “I could have laid there for months,” he says.

Half a year later—an NFL eternity—Jackson still hurts. He hurts worse than when his heart literally gave up, five years ago; worse than when his mom deteriorated past the point of being able to recognize him; worse than when he watched so many family members pass away.

Why? Hue Jackson hurts this much because he defines himself first and foremost as a football coach, and the Browns decided they’d rather pay him to sit at home than to coach their team. He hurts because he is human, because there is a person behind all the memes, a man beyond the punchline, a proud and once-successful coach behind the laughingstock. Everyone knows why Jackson was fired—the losing is public, the record there to see. Few see the private pain.

Jackson says he’d never experienced depression before last fall, never descended so deeply into unending gloom. He refused to turn on the television, knowing he might stumble across the ridicule. He ate only when Michelle delivered him meals. He worried about his three daughters, his mentors, even his old team. He was certain he had failed all of them.

Nine months later the 53-year-old Jackson reclines on his backyard patio in Cleveland. It’s July, and he’s surrounded by a pool, a slide, a sprawling lawn and a river sparkling in the distance. A sliver of tequila fills the bottom of his glass; Chipotle leftovers line the kitchen counter. Chino, the family’s golden doodle, settles at his feet.

All is not well, though. Twenty-five minutes to the southeast, the Browns are beginning training camp, their Super Bowl prospects brightened by rainbows of optimism. Jackson, meanwhile, will move away from the area permanently, to Cincinnati, in a few weeks.

Everything feels unnatural, out of sync. For each of the previous 32 summers Jackson reported to a football field, identified as a football coach. Just a year ago he told his players they should forget their 1-31 record of the past two seasons, that the losing would end right then.

Instead, more losses. For weeks after Jackson’s firing his presence cast “a dark shadow,” says Michelle. Friends sent hopeful text messages and proposed excursions—anything to rouse Jackson and imbue purpose. Only he didn’t want their sympathies. He refused to accept all their View the losing as your experience rather than your identity self-help crap. STOP TEXTING ME, he’d tap back. They had it all wrong. “Football is what made me feel like who I am,” he says. “People might say that’s too far. No, it’s not. You can’t be good at what you do if you don’t pour all of yourself into it.”

Eventually Jackson went back upstairs, stepped outside, saw the sun again. He heard the ghosts. His deceased mother: I didn’t raise you this way. The late Al Davis, the first man who made him a head coach: Get up; let’s go. And he prayed and prayed, mostly asking God for another chance to be a football coach, sadistic as it sounds.

That hasn’t happened yet. It may not happen ever. For now Jackson is a Dance Dad who drops off the youngest of his three daughters, nine-year-old Haydyn, at practice. He’s a voracious reader and a budding businessman. (That glass of tequila? He has a partnership with the maker.) And a workout machine who often hits the gym twice a day. In the months since he started to climb out of his funk he’s killed a relative abundance of newfound free time by following the Lakers, familiarizing himself with his finances, changing a few lightbulbs and getting to know the family he ghosted over so many football seasons. In most ways, he’s never been more human, more normal. And he hates that.

In truth, he’s bored. Really bored. There are only so many books to read, so many sprints to run, so many businesses to partner with. He’ll be recognized by a cashier at his favorite burrito spot and, sure, they’re all kind, all supportive—but part of him wonders what they really think. Jackson’s dark period, his wife says, “is still going on.”

This all comes from the same place, from the soul of a coach who’s watching for the first time in an eternity as a season starts without him. But what complicates any emotional response to Jackson’s situation is the fact that he’s not just a gridiron lifer but a two-time former head coach who never posted a winning season, who lost every game in 2017 and who holds an 11-44-1 career mark, the second-worst winning percentage in NFL history.

Jackson says before he sits down that he won’t trash the Browns. Attempts to explain himself or what happened in Cleveland have not gone over well in the months since his firing. Following a series of interviews he was criticized for blaming others, for taking credit for the team’s eventual resurgence and for being detached from reality, specifically when he told Charlotte-based radio station WFNZ that he did “probably some of my best coaching” throughout all the losing.

He won’t get into the Cleveland tanking operation that he took over, cutting good players to shed salary, letting Pro Bowlers walk, trading down in drafts to stockpile future picks. He knows that such sentiments could sound like excuses, that his detractors would point out the team he left went 5-3 in his absence.

He’s not asking for empathy, although maybe he deserves some, being that he’s a man with an inspiring life story, a minority coach who grinded his way to the top of his profession, a mere mortal forced repeatedly to confront tragedy and death. He understands the baseline, though. He knows that, even as an otherwise successful football leader—one who led the Raiders to 8–8 in 2011; whose teams were a combined 130-109-1 before he arrived in Cleveland, certainly good enough for sustained NFL employment—he will now and possibly forever be known for one disastrous failed tenure. For 3-36-1.

He vacillates. That is him. ... That is not him. “I’m not a loser,” he says. “So that bothers me. I’m not built that way. I hate losing, and it hurt every day. It ground me down every freakin’ week.”

He pauses, his face twisted in an involuntary grimace. It still hurts. “Let’s be honest. Right now, that’s what’s on my tombstone.”

How Jackson wishes he could call his mother, Betty Lee, his hero and single greatest influence, and talk through all of this. For years she worked as a cook, holding two jobs throughout her son’s childhood, and still she found time to drive the boy she called “Huey” to school and to practices, steering him clear of the dangers lurking everywhere in their South Central L.A. neighborhood. “Work for what you want,” she told him. He never forgot that.

“Work was her stress release,” he says. “It was easy for her.”

Jackson’s dad, John Sr., was a commercial airline painter, and he had four children with Betty Lee. The oldest, Yvonne, died suddenly at 33 after her lungs collapsed unexpectedly. To Hue she’d been like a second mom. The next oldest, a boy named after his father, fell into the street life, wasting his athletic gifts—“You name it, he was probably involved in it,” Hue says—and landing in prison for life starting in 1982, during Hue’s senior year at Dorsey High. “He was the guy we all thought was going to be everything,” says Jackson, who stops and thinks about it. There’s “just me and my younger sister” left, he says.

The remaining Jacksons turned inward, relying on one another. They’d drive to Texas and Louisiana for vacation, and on one trip John Sr. crashed the family car head-on, on the highway, killing a passenger in the other vehicle. The engine in that car ripped through the Jacksons’ front windshield, grazing Hue in the face and severing his eyelid. The nightmares lasted for months as his peers taunted him at school. But Jackson channeled all that, the jokes and the pain, into motivation. Which he applied to sports, first at Dorsey, in basketball and football, and later at Pacific, again in both.

Even back in high school his teammates referred to him as “coach,” as if he was destined to lead men. It took nine jobs, for six different teams, before he reached that goal in the NFL, and once there, hired by the Redskins as a running backs coach in 2002, he never stopped climbing, never considered another life. He didn’t have to. He was good at what he did.

Wideout T.J. Houshmandzadeh played for four franchises and more than a dozen coordinators and position coaches across his 11-year career. And he says he found Jackson, who he overlapped with in Cincinnati for three seasons, to be more honest and more detailed than any other coach. With the Bengals from 2004 to ’06 Jackson would meet with his receivers on Thursday nights, ordering Chinese food or pizza, asking them about their families and about politics, weighing life as a black man in the U.S. He told his Bengals charges about his mom’s mounting health problems, his brother’s sentence and how hard it was to be a minority coach in the NFL.

Jackson also taught his players that loss was a part of life, allowing them to see him as vulnerable. “People see Hue on television, they know what he makes, and they dehumanize him,” Houshmandzadeh says. “He carries s--- into his day like everybody else.”

In 2011, four games into Jackson’s tenure with the Raiders, Al Davis, the man who hired him, fell ill. The owner called his new coach before a road trip to Houston to tell him: 1) “You’re doing a good job” and 2) “Don’t let anybody sit in my seat [on the team plane].” He died the day before the game. The Raiders fired Jackson and his staff at the end of the season.

Hue Jackson first noticed his health deteriorating back in 2014, during his second stint with the Bengals, when he was their offensive coordinator. Michelle saw the signs, too, how he “slept football,” his eyes fluttering late at night, as if in deep, tortured thought. On a beach vacation around that time Jackson struggled to maneuver through the sand. Stress now impacted even his ability to walk.

That spring Jackson was on a morning jog on the levee near downtown, chasing another runner in the distance, when he started to lose his breath. He went back to his Bengals office and bent over in dizziness. His chest felt heavy and so he went down to the training room, fearing that he might black out. Trainers sent him to the hospital in an ambulance.

There a surgeon leaned down and told the coach, “If you don’t have surgery right now, you’re gonna die.” Doctors eventually affixed a stent to Jackson’s coronary artery, which they later told him had been fully blocked.

Jackson blames his genes for the incident—his father had two heart attacks, maybe three. That and the fact that he’d stopped taking his cholesterol medicine because it made him feel tired. He doesn’t believe it was coaching that almost killed him.

Michelle is less sure about that. She saw how the stress wore on her husband, how he’d often run out of time to exercise, how he’d leave home at 4 a.m. and return at midnight. Then he started to have episodes, similar to panic attacks, that both Jacksons describe as non-epileptic seizures. Anxiety would overwhelm him and he would black out, briefly losing consciousness.

“I’ve gotta keep going,” Jackson would say, waving off Michelle’s pleas to call 9-1-1. “I’m O.K.”

Through it all, Jackson never took time off, never called in sick. He shuttled his family across the country, moving more than 10 times, by his recollection, in three decades; he missed recitals and graduation ceremonies and prom pictures—“90 to 95% of the girls’ lives,” Michelle estimates.

Yes, it was all part of the (high-paying, prestigious) gig, but it was also what defined Jackson, the ridiculous hours that coaches keep. He loved his wife—the woman he told on the first day they met that he would marry her—and cherished his children. But football would always come first. He buried his problems and ignored the toll exacted by his job. He would joke to his daughters, “Don’t marry a coach.” Then, always, he would retreat to the place that made him feel better: his office.

The worst year of Hue Jackson’s life started not on a football field but at Corcoran (Calif.) State Prison, where John Jr. died the week before Browns training camp opened last July. Jackson still doesn’t know exactly what led to his 59-year-old brother’s death; prison officials explained only that he wasn’t sick and that he’d “bled out.”

Two weeks later Betty Lee died from dementia at age 83. Her health had been worsening for years, but the timing was unexpected. By the end she was addressing Hue as her brother, not as her son, and it crushed him that she couldn’t revel in so many of his accomplishments. She didn’t know that in 2015, when he was with the Bengals, the Pro Football Writers Association had named Jackson its Co-Assistant Coach of the Year. Or that, he says, he had been offered an interview for the Giants’ head opening in ’16. Or that he had passed up that opportunity—and walked away from a handshake deal with Bengals management to succeed his mentor, Marvin Lewis, whenever Cincinnati’s coach retired—for the Browns job, even though he knew, as Lewis says, “that few minority coaches have gone into great situations.” She never got to hear about how Jim Brown called to congratulate him on getting the Cleveland gig and told him that his story as an African American coach mattered. Or about the first time her son addressed his new Browns players, telling them, “Change is here. Change is now.”

She missed the losses, too: 15 in his first season, all 16 games the next year. And with that came more stress, more work, longer hours, more blackouts.

After Jackson got the phone call that Betty Lee had died—in a gutwrenching scene that played out for cameras on HBO’s Hard Knocks—he scheduled her funeral for an off day. He stood in front of mourners and spoke about how she’d “kept everything together,” then he returned to practice. He still had two families to hold together.

“I started looking around my life,” Jackson says, “wondering, Who’s next?” Not that he had any time to pause, to grieve. That much was underscored by a more titillating scene in Hard Knocks that captured his Browns assistants, particularly offensive coordinator Todd Haley, openly questioning the head coach’s authority during a meeting. Viewers saw the drama, but not the human toll, the body breaking down.

Early on most mornings, before sunrise, Jackson would call Tommy Shavers, a motivational speaker he’d years ago befriended, and express his deepest fears. He worried about his own job, his assistants’ jobs and their families; he worried about the ripple effect of all the losing. He knew the toll extended far beyond his own health.

Shavers would remind Jackson that the fans who crushed him were human, too; that they were also invested; that they might not know all that he’d overcome. Or might not care. That player-coach-fan dynamic would never be rational or healthy or empathetic. Shavers had counseled numerous coaches across the NFL, and every time he entered a facility in crisis he could feel the weight of every decision, even on the faces of the secretaries.

“You can’t ask fans to separate the losses from the person,” he would tell Jackson. “Coaches sign up for that. If the victories are part of their legacy, the losses should be too. You don’t hear anyone saying, The wins don’t define me.”

“I get it,” Jackson told him.

“Hue knew there was only one answer, one solution,” Shavers says now. “Win.”

Jackson says he truly believed his Browns could prevail in nine or 10 games last season if they could only overcome the stigma of their losing past. And he thought one player in particular could help the franchise make that mental leap: Oklahoma quarterback Baker Mayfield, whom general manager John Dorsey had selected with the first pick in the 2018 draft. “This,” Jackson told Houshmandzadeh, “is exactly the guy we need.”

Then, head-scratchingly, he started veteran Tyrod Taylor, a move that struck many as save-my-job, play-it-safe desperation. Taylor eventually left a Week 3 game against the Jets with a concussion, and Mayfield led Cleveland to a rousing comeback victory, ending the league’s longest losing streak. Still, the Browns fell to 2-5-1 at the halfway point.

Where Jackson saw progress, like the four overtimes his team forced in 2018, Browns brass saw something worse. In dismissing the coach they told him he had lost the team, that his staff had fractured and that they were sick of all the infighting.

In autopsy mode, Jackson is careful to own his culpability and not trash his old team. Still, he needs to explain what happened, which leads him to push back, for example, against the notion that he self-promoted, that he “performed” for the Hard Knocks cameras (as has been suggested) and, most strongly, that his team had stopped fighting for him. “If you’re in that many overtime games,” he says, “I don’t think there’s any way you could [say that].”

As for Mayfield, Jackson says he advocated for the pick, but he admits he didn’t develop the same depth of relationship that he’s had with other QBs throughout his career.

If he could take anything back, do anything over, he would never have relinquished control of the offense to Haley, who handled playcalling and gameplan duties in 2018. He says he would have bet on himself, which only prompts more questions. Why was it so easy to under-cut the head coach? Why did he hire Haley in the first place? And why didn’t he simply take the offense back?

Jackson says the Browns’ front office dynamic wasn’t set up for him to reclaim offensive control with one unilateral decision. (When he told reporters after a loss at Tampa Bay last Oct. 21 that he wanted to “help” more with the offense and then assumed a more active role, it only caused confusion and animosity, according to a source within the organization.) But mostly Jackson waves it all off. None of it matters. As the man in charge, the responsibility and the record lie with him.

Jackson accepts that he could have built better relationships with his assistants, set a clearer tone. He knows in his heart that when a team loses 31 games in two years it does so together, that it’s never just one person at fault. But he also accepts that he was the face of those teams and that he has to live with it.

“I failed tremendously,” he says. “Regardless of how you look at it.”

In the aftermath, social media did what it tends to do with such epic failures, turning Jackson into a national joke, inspiring headlines like HIRING HUE JACKSON A CATASTROPHE WAITING TO HAPPEN FOR NFL TEAMS. Beneath the snark, critics piled up the fair points. Jackson’s Browns did win just one of eight overtime appearances in his tenure. They did win only 37.5% of the time when they forced more turnovers than their opponents, compared to a league average over 75%. Mayfield did improve markedly after Jackson’s dismissal, cementing his status as one of the NFL’s most promising young QBs.

Ultimately, it wasn’t the public response that stung Jackson worst. Sure, he hated when Haydyn was teased by classmates at school or when strangers lit him up online. But Clevelanders, for the most part, remained friendly, as he tells it. They would console him at the gym or in the airport, telling him he’d laid the foundation for the team’s impending success, that he’d handled himself the right way, that they were proud of how he’d picked himself up, week after terrible week. What else would they say, standing right in front of him? It didn’t matter, though. The losses—those are what really bother Hue Jackson.

He knows he will never control the worst perceptions about him. When Lewis called up last November, after Jackson had crawled out of the guest room, and offered up a lifeline gig as a Bengals assistant, Jackson accepted. To some this move to a division and state rival appeared shady. Mayfield, for one, called him out as “fake.”

Jackson sees it differently. He was depressed, his wife was worried about him and his best friend did him a solid. “I needed that jolt,” he says. “[Marvin] helped me. What he did wasn’t about football. I don’t know what would have happened had he not.”

The difference between the public and private narratives was perspective. Lewis saw Jackson as a human being; Mayfield saw only a football coach.

As for the result of their next interaction, a Dec. 23 game in Cleveland during which a victorious Mayfield threw three TDs and stared down the new Bengals assistant on the sideline, Jackson wrestles back a little credit. “Now that they were playing good football, it was easy to say it was because [I was] not there,” he says. “I don’t think that was the case. I think that’s where it was trending.”

Still, when he says aloud that he holds no ill will toward Mayfield, and that he wants the Browns to keep winning, it can come across like he’s trying to convince himself. “People are going to feel the way they feel,” he says. “Baker’s Baker, and I’m gonna be me.”

Down in Jackson’s basement, framed snapshots of family members and of football glory line the walls on either side of the guest bedroom where he sulked last Halloween. “I don’t want to come down here,” he says, “because I don’t want to see all this. This is for when it’s over. And my story’s not finished yet.”

He won’t consider that perhaps it’s time to segue into a second life, that his record might be the one thing he cannot overcome. He refuses to view his career as something he worked decades toward and failed at. He sees, instead, three years of abject disaster sandwiched between a past filled with accomplishment and a future teeming with promise. It’s tough, in conversation, to tell whether he admits that he failed because he believes it, or because he knows he has to. Because he recognizes his mistakes, or because he desperately wants back in and will say anything to make it happen.

That makes him more human, though, not less. It’s why when he drives his daughter to dance practice, three miles from his old Browns office, he always takes a different route from the one he followed every day to work.

He’d rather be coaching, not sipping tequila,. Not getting more sleep than he has in 30 years. Not touring his foundation, which helps vulnerable women escape human trafficking, his efforts there worthy of a humanitarian award from Harvard and yet not the same as what he wants most. “If some team called tomorrow...” he says, trailing off.

He does, occasionally, think about escaping. He holds up his phone, proudly displaying his nearly three million Marriott rewards points. He could live in any hotel for months, anywhere in the world. He could sit on a beach in Aruba rather than steer around the mementos in his basement, the reminders of his past.

It’s just that he can’t stand that word. Loser. He vacillates. That’s not him. ... O.K., it is. ...

“I don’t look at the record and think, You’re a loser because you lost,” says Michelle. “I look at the years and years of dedication, studying, learning, overcoming. That’s winning. The human part.”

Hue appreciates the sentiment, but his head moves back and forth as his wife talks, reflexively signaling disapproval. He is and will forever be a football coach. And football coaches—the good ones, anyway—they win.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.